Dr Steven Reid is a lifelong member of Royal Lytham & St Anne’s Golf Club, an author and historian with more than a slight interest in the life of Bobby Jones. After our podcast discussing the 1926 Open Championship (brilliantly chronicled in his book; ‘Bobby’s Open‘, talk turned to the famous Berrie portrait which was commissioned by Wallasey member and ex-captain Sir Ernest Royden, and painted by John A.A.Berrie.

In this excellent article, Steven takes us closer to how a portrait from 1930 came to become the most iconic image of Bobby Jones and one that we all recognise from Butler Cabin at Augusta National.

‘The Berrie Portrait‘

words by Dr Steven Reid

Table of Contents

Share This Story

The Wallasey Portrait

When Bobby Jones played at Wallasey Golf Club in 1930 in order to qualify for the Open to be played at nearby Hoylake, an ex-Captain of the Wallasey Club, Ernest Royden, commissioned J.A.A. Berrie, R.A, and a fellow member of Wallasey, to produce a portrait in oils of the Georgian golfer. The sitting took place on the Sunday morning before the Open started.

At that time, Berrie was Liverpool’s leading artist. Born in 1887, the list of those who sat for him included King George V, King Edward VIII, Winston Churchill and Earl Mountbatten of Burma. On a more local level, many of his portraits are on display on the staircase and walls of the Artists’ Club in Eberle Street, Liverpool.

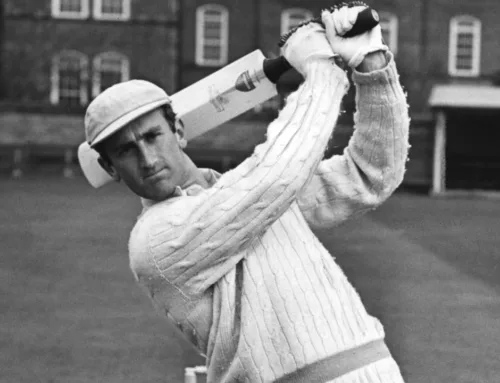

The Wallasey portrait shows Jones from the waist up. When Berrie had completed his preparatory work, Jones removed the blue sweater he was wearing and gave it to a Wallasey member, who put it on to sit for Berrie, in order that the painting from the neck down could be completed. Before leaving the studio, Jones was sufficiently taken with what he saw to sign and date the lower right corner, the only time he ever did so. Subsequently he so liked the outcome that he had a copy produced which hung ‘in my home, where it always attracts attention and admiration.’

The sitting at Wallasey was completed in remarkably little time. In a subsequent letter, Jones recalled: Mr Berrie kept me occupied for not more than thirty minutes and during that time pleasantly refreshed with a whiskey and soda. As an object lesson in painless portraiture, this was the best I have ever seen.

That might have been the end of the story had it not been for the intervention of John Rothwell Dixon. Much of the information about Dixon has been drawn from an excellent article written by his grandson Phillip Stern, with the title Portraits of the Artist as a Young Man, which was posted on the Royal Liverpool website. Born in Great Marton near Blackpool, Dixon became a member of what was then the Lytham and St Anne’s Golf Club. Like so many of the members of the Club at that time, his business interests were in East Lancashire, where ‘cotton was still king’.

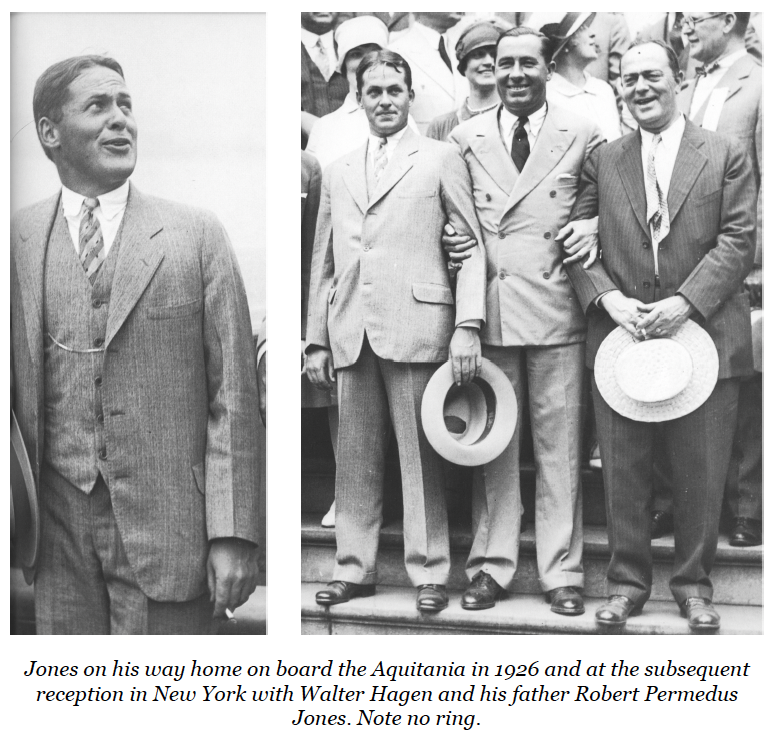

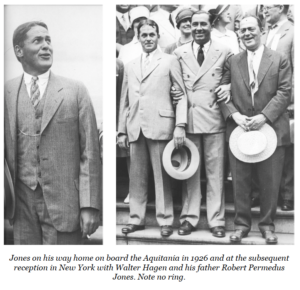

Although he moved to the Wirral in around 1913 after his marriage, his golf was still based at St Anne’s and he became Captain of the Club in 1926, the year in which the Open was to be played here for the first time. By this time, he had assumed control of three cotton mills in Blackburn, which he ran from his offices in Manchester.

He was taken ill a few days before the Open and this precluded him from presenting the Claret Jug to the winner, Bobby Jones, that task falling to Brigadier- General Topping. Doing so had unfortunate consequences for the Brigadier, who caught pneumonia shortly afterwards and died, his death being reported at the next Council meeting.

Dixon missed much of his year as Captain with health problems and once he had recovered, the Club elected him Captain for a second year in 1927. When Bobby Jones was elected to be an Honorary Life Member in 1931, Dixon marked the event by commissioning Berrie to produce a further portrait, which Dixon presented to the Club.

For much of his life, Dixon remained actively involved with Marton, where he was, until his death, president of the working men’s club there, which had been founded by his father, John Picken Dixon.

As well as his generous presentation of the Jones portrait in our Clubhouse, he also commissioned and presented the Jones portrait which hangs at the top of the staircase in the Clubhouse at Hoylake, where Dixon was also a member. He went one step further and commissioned a portrait of himself by Berrie, so the original Wallasey sitting turned out to be very productive for the artist.

The Royal Lytham Portrait

Students of golf will know that The Masters was brought into being by two men – Bobby Jones and Clifford Roberts. In the 1970’s, Roberts came to Royal Lytham and St Anne’s and past Captain Colin Maclaine took him to see the portrait. Colin said to him: This is thought to be one of the best paintings of Jones.

Roberts fell silent for a short time and then, turning to Colin, said, quite simply: It is the best. Indeed, he was so taken with it that he persuaded Colin to have a copy created, which now hangs in the Clubhouse at Augusta National.

Cradled in his left arm, Jones holds a hickory shafted club. Just before he came to Lytham in 1926, he discovered this club at Sunningdale Golf Club and used it in winning not just here, but also in all nine further Majors he won in the years that followed. It was given the name Jeanie Deans, after the heroine in the Walter Scott novel The Heart of Midlothian.

The Ring

In the portrait, there is a sizeable ring with an impressively large diamond visible on the ring finger of his left hand. This ring was his wedding band and the diamond came from his mother’s engagement ring. In the years after his marriage in 1924, the ring is a variable item in the many photographs taken of him. It is visible in a photograph of him with a dog in 1925 and at various trophy presentations after 1926. The ring has not been identified in any photographs taken during his 1926 trip to Great Britain and he may well have sensibly decided to leave it at home, rather than risk bringing it with him on the trip. There was, after all, a General Strike looming here.

He did wear it when being presented with the Open claret jug at Hoylake in 1930, and he may have worn it when at Wallasey. The only times that Jones and Berrie were in each other’s company was at that brief sitting in 1930. Jones was in casual clothing at the time and whilst the ring is not evident in the Wallasey portrait, it may have caught Berrie’s eye. Photographs taken as an aid to the portrait preparation may have included the striking ring.

It was some time later, in 1931, that Dixon commissioned our portrait. After Jones retired from competitive golf, he made a series of instructional films for the Warner organisation. In the photograph below, the ring is on Jones’s left hand, which inevitably also holds a cigarette. The make up department appears to have been in action.

The Painting’s Legacy

To this day, the Berrie portrait at Royal Lytham and St Anne’s is a focal centre of interest in the Clubhouse.

Looking at the face and eyes in the portrait, the gaze is compelling and striking. When Jones met an opponent on the first tee, he would offer him a firm handshake and look into his eyes. He later said: I had held a notion that I could make a pretty fair appraisal of the worth of an opponent simply by speaking to him on the first tee and taking a good measuring look into his eyes. If you were the opponent, one can only imagine the impact this would have had on you.

A century after he won his first Open Championship, his gaze is as penetrative as it was in his playing days. At the same time, it conveys honesty, integrity and decency. For one glorious decade he lit up the world of golf and of sport in general.

It was not just his golf, but also the qualities of his nature that he brought into the game which have led students of the game to continue to respect and admire all he did nearly a century ago.

Dixon clearly admired the work of Berrie, for as already mentioned, he also invited the artist to produce a portrait of himself. The result is a striking likeness which remains with his descendants, who have kindly given permission for its inclusion with this article.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Philip Stern of the Royal Liverpool Golf Club for the elements drawn from his article.

Thanks are due to the Wallasey Golf Club for the opportunity to see the portrait there.

Thanks are due to the Dixon family for permission to include the John Dixon portrait.